I am currently looking for therapeutic targets in HPV driven cancers. Human Papilloma Viruses infect keratinocytes (keratin producing cells) on the outer and inner surfaces of the body and replicate therein, and some of the subtypes of the virus cause warts…ugly and disfiguring, but some have effects far more sinister – they can, following sustained infection, lead to the development of cancer…we call these subtypes “High-risk".

A slide of cervical squamous cell carcinoma.

Some are spread by skin contact (the low risk types, which can cause warts) and the high risk types are primarily spread by sexual intercourse, and it really isn’t surprising that they mostly cause cancer in the uterine cervix, and rather increasingly of late, in the oral cavity. Cervical cancer is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in women, and is especially devastating in low-and-middle income countries, where screening is not readily accessible.

While head and neck cancer that is driven by HPV confers a better prognosis

compared to HPV negative head and neck cancers, there isn’t much difference in treatment, which can involve some horribly disfiguring surgery to resect the tumour, and therefore it is imperative that targeted therapies be developed.

HPV infected cells can only survive because the viral proteins, E6 and E7, primarily bind to, inactivate, and induce the degradation of two classic tumour suppressor genes (which basically stop cells from dividing out of control by arresting growth or inducing suicide) – pRb and p53. It has been known for some time that infected cells need those viral proteins to survive because knocking them down results in reactivation of those tumour suppressor genes and consequently, cell death. My job is to look at whether there are other changes induced by HPV infection that are necessary for those cells to survive, and to establish those changes as therapeutic targets.

In order to identify targets to screen for, I used some fancy computer programming to interrogate gene expression microarray datasets from different studies that are publicly available in databases such as the Gene Expression Omnibus, comparing HPV driven cancer cells and HPV infected cells versus HPV negative samples to find out which genes were overexpressed or underexpressed in the former relative to the latter signficantly enough to be unlikely due to chance and pulled out a set of genes to screen.

A representative microarray heatmap, used to visualise differences in expression between two biological classes, in this case, HPV positive and HPV negative samples.

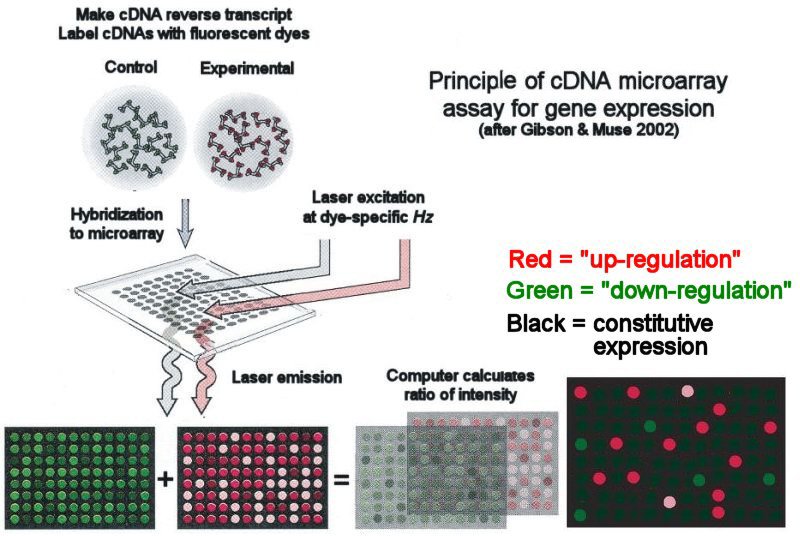

Microarrays are basically slides containing probes for all the RNA transcripts produced by the human body, to identify an expression profile, we make DNA from RNA using reverse transcriptase, and then label it with a fluorescent dye, and then chuck them onto the array. The intensity of fluorescence at a particular probe will be directly proportional to the amount of the transcript, and we can therefore quantify gene expression.

Schematic of a differential expression array experiment, where we throw in two different samples onto the same chip.

Because probe fluorescence is amenable to numerical representation, I was able to retrieve results of multiple different studies from different groups and pool them together to identify an expression signature.

One way we test if expression changes are essential is using models for studies, and I am using a panel of Head and Neck Cancer Cell lines at the moment. To make sure they were suitable models, I had to confirm that the expression changes I had identified were being recapitulated in these lines. To do this, I pulled RNA out of the cells (since RNA levels are a decent indicator of expression levels), converted it to complementary DNA, and ran a quantitative PCR reaction to check for differences in levels (and as a consequence, expression).

Also, to confirm that the E6 and E7 oncoproteins were causing the changes I inferred from my computational work, I did the same thing with cells into which those proteins had been introduced.

That said and done, I have been preparing to screen for the effects of knocking down the genes that are overexpressed in my signature for HPV driven cancers using some really cool technology. I will be applying RNA interference to silence my genes using little hairpins of RNA targeted against the mRNA they produce.

I am currently engineering little viruses to deliver those hairpins to target cells. To do this, I basically make copies of DNA plasmids that encode those hairpins, which are of the pGIPZ type in bacteria, grow them up, and extract and clean up said DNA. I put the DNA together with a transfection reagent and two other plasmids that contain proteins that help package the construct into a lentivirus, which, unlike a retrovirus, can infect non-dividing cells as well, into 293T cells, which, because of the activity of pGIPZ inside them once the vector has integrated, glow green due to the production of GFP, a green fluorescent protein encoded for by the pGIPZ plasmid, like so.

I have since then gone on to test which one of my constructs disables the expression of my target genes the most by infecting cells with viruses that the transfected 293Ts produced and carrying out qPCR, and in the next few weeks, I will be infecting all the cell lines I’ve got to see if I can selectively inhibit the growth of/kill HPV+ve cancer cell lines. And then, things will have just begun on the path to discovering effective therapeutics against these targets…

and this is what some types of cancer research look like...